ITAK, DTNA and TNPF: Need for recalibration without capitulation

[TamilNet, Monday, 19 January 2026, 14:44 GMT]

The present moment in Tamil politics demands far more than tactical adjustment or rhetorical caution. It demands a fundamental reassessment of the assumptions that have gradually come to govern political engagement since the end of the genocidal war in 2009. What is at stake today is not merely the content of constitutional proposals, but whether the Tamil political project itself is being quietly stripped of its historical, legal, and moral foundations. This erosion has not occurred overnight. It has unfolded through a slow narrowing of political imagination, in which positions once regarded as foundational have been recast as impractical, excessive, or even dangerous.

The most serious consequence of this shift is the growing tendency to treat self-determination as a negotiable aspiration rather than as a right that precedes and constrains constitutional design.

The danger of this approach became particularly evident when sections of Tamil political leadership, most notably within the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), acceded to the Aekiya Rajyaya framework and its logic of indivisibility in 2019.

What was once treated as a provisional political position gradually hardened into a constitutional assumption.

This shift did not emerge from public debate or collective endorsement, but through gradual accommodation.

The forfeiture in question was effected under the leadership of the late R. Sampanthan and the late Mavai Senathirajah, with M.A. Sumanthiran playing a central role, despite the absence of clear support from a majority of TNA parliamentarians.

At this point, a clear distinction must also be made between the Aekiya Rajyaya framework and what the TNA actually placed on record in its 2020 constitutional submission.

The TNA’s constitutional proposal, while politically cautious and limited in scope, does not constitutionally extinguish future political choice, except for a preambular reference to Sri Lanka as “undivided and indivisible.”

That reference remains declaratory rather than operative.

It does not translate into binding constitutional mechanisms that permanently foreclose the Tamil people’s right to re-determine their political status.

In this sense, the TNA proposal reflects political restraint rather than legal closure.

The same cannot be said of the Tamil People’s Council (TPC) framework.

While the TPC invokes the language of self-determination, it embeds the principle of indivisibility as a governing principle through operative clauses.

What appears to be recognition becomes negation.

Self-determination is acknowledged in theory, yet structurally disabled in practice. This is not a compromise; it is a contradiction.

A right that cannot be exercised is no right at all.

* * * The false Federal–Unitary debate and the Aekiya Rajyaya trapA further distortion has emerged through the manufactured debate between “unitary” and “federal” models.

The

Aekiya Rajyaya / Orumiththa Nadu formulation was introduced precisely to avoid this binary, presenting itself as a supposedly innovative middle ground.

In reality, it has functioned as a semantic device designed to accommodate Sinhala majoritarian anxieties while disarming Tamil political resistance.

This has created a dangerous illusion. The debate has been redirected toward terminology rather than substance, allowing constitutional structures of control to be smuggled in beneath conciliatory language.

The result is a framework that is neither genuinely federal nor merely unitary in disguise, but rather more restrictive than either in its practical effect.

The danger of the Aekiya Rajyaya formulation lies precisely in this ambiguity.

It does not merely dilute Tamil political rights; it explicitly denies their basis.

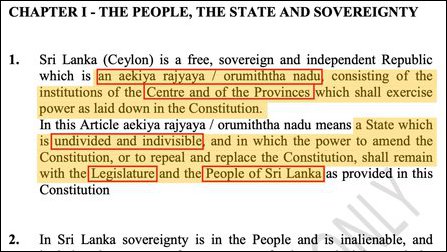

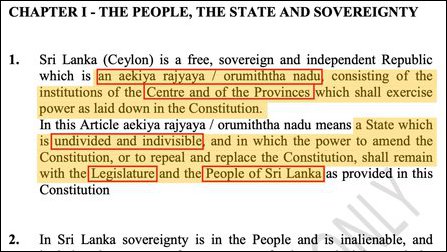

Aekiya Rajyaya/Orumiththa Nadu clause as defined in the 2019 Discussion paper

By rejecting ethno-national identity and asserting the existence of a single “People of Sri Lanka,” the Aekiya Rajyaya framework does not simply constrain self-determination of the nation of Eezham Tamils; it negates the very subject entitled to exercise it.

Self-determination is not just limited; it is rendered legally incoherent. This makes it more insidious than an openly unitary model.

This ambiguity has also provided cover for sections of Tamil political leadership to divert debate into semantic disputes, falsely equating criticism of the Aekiya Rajyaya framework with opposition to the unitary state itself.

In doing so, the real issue has been obscured: the constitutional entrenchment of indivisible sovereignty that forecloses meaningful political choice.

* * * TNA and TPC: crucial difference of consequenceAt this point, a clarification is necessary.

While the 2020 TNA (nowadays Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kadchchi/ITAK + Democratic Tamil National Alliance/DTNA) proposal leans towards devolution within a unitary framework that borrows federal features, the 2016 TPC proposal leans towards a federal-looking structure that retains unitary character at its core.

On the surface, this might suggest that the TPC approach is more progressive.

In reality, the opposite is true.

The TNA proposal, despite its limitations, does not structurally preclude future political re-determination. Its weakness lies in political caution and under-assertion, not constitutional foreclosure.

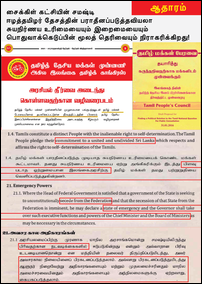

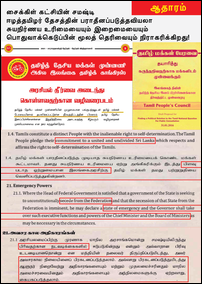

The operative clauses 1.4 and 21.1 of the TNPF/TPC proposal jointly operate as "nuclear option”

By contrast, the TPC/TNPF proposal

embeds indivisibility as an operative principle. It constitutionalises the limits of Tamil political aspiration while simultaneously claiming to recognise self-determination.

This is what makes the TNPF/TPC framework more dangerous than it appears. By presenting itself as a middle path, it normalises a deeper form of closure. It converts self-determination into a symbolic gesture rather than a living right.

The danger is not that it is insufficiently radical, but that it is internally designed to prevent future choice.

It is therefore not accurate to suggest that the TNPF/TPC represents an advance over the TNA (ITAK+DTNA) position.

In constitutional terms, it represents a regression.

* * * Responsibility, not rhetoricThis places a particular responsibility on the ITAK.

As the largest Tamil political party with parliamentary representation, ITAK carries a historical obligation to act with statesmanship rather than mimic the performative politics of smaller actors.

The temptation to engage in press politics, social media posturing, or rhetorical one-upmanship may yield short-term attention, but it erodes long-term credibility.

Tamil politics does not need louder slogans.

It needs clarity, consistency, and solution-oriented seriousness.

The TNPF’s reliance on rhetoric unaccompanied by structural coherence has exposed the dangers of reducing politics to symbolism rather than substance.

The ITAK must not follow that path.

Its role is not to compete in theatrics, but to defend the political space in which the Tamil people can exercise a real choice, not one pre-scripted to be revocable through devolution within an indivisible unitary state.

The TNPF has increasingly advanced, both directly and indirectly, its narrative in recent engagements in Tamil Nadu and Europe, presenting federalism as a superior interim solution that does not contradict long-term political aspirations.

This framing is completely misleading.

The TNPF/TPC proposal is structured around a constitutional “nuclear option” that extinguishes the right to a referendum and forecloses self-determination altogether. In that sense, it cannot even be described as an incremental position.

By contrast, the TNA proposal, despite its limitations and problematic preambular language, leaves the path open at the operative level. The difference is not rhetorical but structural.

The TNPF model fails because it cannot achieve a meaningful balance between principle and pragmatism, leading to the conclusion that it does more harm to the Tamil political position in the long run than even the flawed compromises associated with ITAK.

* * * Reclaiming political horizonThe demand for a referendum and the assertion that decolonisation remains unfinished are not extremist positions.

They are the most accurate and legally grounded expressions of the Tamil political condition.

The right to self-determination was never exercised at decolonisation. It was denied.

Subsequent constitutional arrangements were imposed without consent. The failure of the so-called internal self-determination did not extinguish this right; it reinforced it.

Nor can this right be nullified by participation in an illegitimate constitutional order. Electoral engagement does not equate to consent. Tactical accommodation does not erase historical injustice.

To argue otherwise is to confuse survival with surrender.

A voluntary political union can only be legitimate if it preserves the right of exit.

Anything less is not unity but entrapment.

The right to self-determination of the nation of Eezham Tamils is not a slogan or a bargaining chip.

It is a continuing right grounded in history, democratic mandate, and international principle.

Attempts to dilute it in the name of pragmatism do not advance peace; they hollow it out.

The choice before Tamil politics is therefore clear. Either it reclaims the political ground that has been gradually ceded, or it accepts a future in which the most fundamental question is no longer open to the people themselves.

What is required at this juncture is not escalation or retreat, but political recalibration grounded in principle.

Tamil politics must recover the ability to distinguish between tactical engagement and the surrender of foundational rights.

Recalibration, in this sense, means restoring clarity about self-determination, refusing constitutional arrangements that pre-empt future choice, and resisting the temptation to exchange long-term political agency for short-term acceptance.

Capitulation occurs when this distinction is lost, when accommodation is mistaken for strategy, and when constitutional closure is accepted in the name of realism.

The task before Tamil political leadership is therefore not to choose between confrontation and compromise, but to ensure that compromise does not become the means by which the right to decide is quietly extinguished forever.

Related Articles:13.01.26

பொதுவாக்�.. 13.01.26

தமிழ்நாட�.. 18.12.25

மறுக்கமு�.. 23.07.25

கறுப்பு ஜ�..

Chronology: